ACCORDION MUSIC: BASIC

1. What is Music?

For the purposes of this web site, Music may be formally defined as any melodic, rhythmic and/or harmonic grouping of sounds that is composed for personal enjoyment, and/or to entertain and/or to inform.

2. From the Source to the Listener to a Representation

Here are a few of the music terms you may find useful. Some of these terms apply to the source of the music where, in the case of the accordion, vibrating reeds generate musical tones that are transmitted through the air as sound waves. Some apply to the listener's hearing and his or her brain's perception of the music. Some apply to a paper representation of the music.

Frequency & Pitch

Consider a source, such as an accordion reed, that oscillates physically at a fundamental frequency of 440 Hertz (vibrations per second).

- This creates a tone that can travel as a sound wave in the surrounding air.

- A very short time later, this wave reaches the listener's eardrums, causing them to vibrate.

- Each ear detects this and transforms it into signals that are sent from the inner ears to the brain, which interprets it as a sound of a certain pitch, that we represent by the label "A". Thus pitch is a mental construct, associated with the frequency of the tone reaching the ears, and thus with the reed's fundamental oscillation frequency.

Your accordion may also have

Each "A" differs from the one above or below it by a pitch separation of one octave. The ancient Greeks noted that pairs of tones, such as those that we now label as A and higher-A, with six tones between them, formed a common musical group of eight tones (or an octave). Our diatonic accordions are based on this, with just over two octaves available on each row.

- a reed that vibrates at 220 Hz, which the brain can interpret as a lower pitch "A", because, though different, it feels to the brain very much like the pitch "A".

- Similarily, a reed that vibrates at 880 Hz, can be interpreted by the brain as a higher pitch "A".

Each "A" differs from the one above or below it by a pitch separation of one octave. The ancient Greeks noted that pairs of tones, such as those that we now label as A and higher-A, with six tones between them, formed a common musical group of eight tones (or an octave). Our diatonic accordions are based on this, with just over two octaves available on each row.

Measured Time & Beats

The measurable length of time, in seconds or fractions of a second that each reed vibrates, depends on the length of time you keep its button pressed and the bellows pushed or pulled. Your brain recognizes durations of time, though not as absolute measurements. That is one of the reasons why, in music, we often use an arbitrary unit of time, such as a regular beat, that the brain can detect, count, and comfortably organize.

Beat intervals can be related to clock-measurable time by giving the rate at which beats are counted, say, in beats per minute (abbreviated bpm). We may refer to this rate as the tempo (or pace) of the music.

Alternatively, I could have said that each beat interval represents a time interval in seconds (s), or fractions of a second. Thus a tempo, or pace, of 120 bpm (120 beats in 60 seconds) corresponds to a beat interval of half a second.

The measurable length of time, in seconds or fractions of a second that each reed vibrates, depends on the length of time you keep its button pressed and the bellows pushed or pulled. Your brain recognizes durations of time, though not as absolute measurements. That is one of the reasons why, in music, we often use an arbitrary unit of time, such as a regular beat, that the brain can detect, count, and comfortably organize.

Beat intervals can be related to clock-measurable time by giving the rate at which beats are counted, say, in beats per minute (abbreviated bpm). We may refer to this rate as the tempo (or pace) of the music.

Alternatively, I could have said that each beat interval represents a time interval in seconds (s), or fractions of a second. Thus a tempo, or pace, of 120 bpm (120 beats in 60 seconds) corresponds to a beat interval of half a second.

Tones & Notes

The term tone is associated with the sound wave created by a vibrating source. Thus we may refer to the frequency of a certain tone as 261.6 Hz (oscillations or vibrations per second), represented by the label "C" (or, on a piano, as "middle-C").

We often use the term note as a synonym for "tone"; however, in formal music notation, it is the paper (or computer screen) representation of a particular tone.

If you press a button on your accordion while pushing or pulling the bellows, you create a tone, such as the "C" used in the previous example. A standard music sheet will represent the frequency of that tone by the placement of a note symbol relative to a group of parallel lines on the paper (or screen), and its duration by the shape of the note symbol. In our accordion notation, we show these notes as button numbers for the push or the pull* to indicate the frequency or the pitch of the tone, with prefixed marks to indicate the duration of the tone, for example '3 .4 ;6* and :6 - more about this later.

The term tone is associated with the sound wave created by a vibrating source. Thus we may refer to the frequency of a certain tone as 261.6 Hz (oscillations or vibrations per second), represented by the label "C" (or, on a piano, as "middle-C").

We often use the term note as a synonym for "tone"; however, in formal music notation, it is the paper (or computer screen) representation of a particular tone.

If you press a button on your accordion while pushing or pulling the bellows, you create a tone, such as the "C" used in the previous example. A standard music sheet will represent the frequency of that tone by the placement of a note symbol relative to a group of parallel lines on the paper (or screen), and its duration by the shape of the note symbol. In our accordion notation, we show these notes as button numbers for the push or the pull* to indicate the frequency or the pitch of the tone, with prefixed marks to indicate the duration of the tone, for example '3 .4 ;6* and :6 - more about this later.

Intensity & Loudness

This is part of the dynamics of a tune. Vibrating accordion reeds can transmit a range of measurable physical intensities to the surrounding air, depending on how powerfully the player makes them vibrate. The brain interprets this in terms of loudness, though not in a simple way. For example, one sound may arrive at a listener's ear with twice the intensity of another sound, and the brain would indeed normally recognize the former as being louder, but would not usually interpret it as twice as loud.

This is part of the dynamics of a tune. Vibrating accordion reeds can transmit a range of measurable physical intensities to the surrounding air, depending on how powerfully the player makes them vibrate. The brain interprets this in terms of loudness, though not in a simple way. For example, one sound may arrive at a listener's ear with twice the intensity of another sound, and the brain would indeed normally recognize the former as being louder, but would not usually interpret it as twice as loud.

3. Standard Music Notation

Music experiences are primarily about playing tunes, singing songs, and listening to others playing and singing. For thousands of years, tunes and songs were passed on from one generation to the next, held in family or community memory. With the development of more complex music (for pianos, symphony orchestras, etc.), it became necessary to develop and standardize very elaborate (and complex) music notations, about which thousands of books have been written. Happily, our button accordions are not complex instruments, and we can use a simpler notation.

Music experiences are primarily about playing tunes, singing songs, and listening to others playing and singing. For thousands of years, tunes and songs were passed on from one generation to the next, held in family or community memory. With the development of more complex music (for pianos, symphony orchestras, etc.), it became necessary to develop and standardize very elaborate (and complex) music notations, about which thousands of books have been written. Happily, our button accordions are not complex instruments, and we can use a simpler notation.

4. Button-Accordion Notation

This site's button-accordion notation is covered in more detail on later pages. At its most basic level, it shows

This site's button-accordion notation is covered in more detail on later pages. At its most basic level, it shows

- the pitch of the notes to be played (and tones to be heard) by their accordion button numbers.

- the relative duration of each note (and tone) by simple punctuation marks before the button number.

- melodic rhythm by repeated pattens of duration and/or relative pitch, often identified as phrases.

5. Octave Alphabet Soup, with Seven Letters

Much of our music is based on twelve collections of notes, with seven notes in each collection. The C collection of notes, if played in succession, would be counted as follows:

C = 1 D = 2 E = 3 F = 4 G = 5 A = 6 B = 7 Higher C = 8

These are counting numbers from 1 to 8, not button numbers.

If played in the order given, starting and ending on C, we refer to it as the C-major scale. These notes form an octave, which can be repeated to reach higher, or lower, C notes. Each treble row of my button accordion covers just over two octaves; on the other hand, a standard piano keyboard covers more than seven octaves.

The Greeks first observed that the notes in an octave were NOT equally spaced in a relative auditory sense. For example, stepping from note to note on the C-major scale would be equivalent to the following:

C step-to D step-to E baby-step-to F step-to G step-to A step-to B baby-step-to higher C

If you have a double-row accordion with a C row, that is what you are playing when you press the following buttons, pushing or pulling as indicated:

3 step-to 3* step-to 4 baby-step-to 4* step-to 5 step-to 5* step-to 6* baby-step-to 6

Much of our music is based on twelve collections of notes, with seven notes in each collection. The C collection of notes, if played in succession, would be counted as follows:

C = 1 D = 2 E = 3 F = 4 G = 5 A = 6 B = 7 Higher C = 8

These are counting numbers from 1 to 8, not button numbers.

If played in the order given, starting and ending on C, we refer to it as the C-major scale. These notes form an octave, which can be repeated to reach higher, or lower, C notes. Each treble row of my button accordion covers just over two octaves; on the other hand, a standard piano keyboard covers more than seven octaves.

The Greeks first observed that the notes in an octave were NOT equally spaced in a relative auditory sense. For example, stepping from note to note on the C-major scale would be equivalent to the following:

C step-to D step-to E baby-step-to F step-to G step-to A step-to B baby-step-to higher C

If you have a double-row accordion with a C row, that is what you are playing when you press the following buttons, pushing or pulling as indicated:

3 step-to 3* step-to 4 baby-step-to 4* step-to 5 step-to 5* step-to 6* baby-step-to 6

|

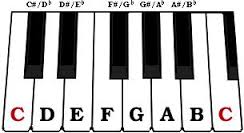

This is easier to follow on a piano, and would be equivalent to starting from middle C (white key), and walking up the inside of the keyboard with your fingers, stepping over any black keys and touching only white keys. Observe that there is no black key between E and F, nor between B and C; hence the "baby-steps" when moving between these keys.

|

Remember the "Step Step Baby-step Step Step Step Baby-step" pattern; musically it defines what is called a diatonic major scale, and the notes form a diatonic collection.

6. Adding Spice to our Alphabet Soup

When your fingers walk up the inside of a piano keyboard, it takes only a "baby-step" to move to the next key, but a full step to skip over a key. Starting from C and following this pattern you step only on white keys. In an auditory sense, remember that a baby-step is said to be equivalent to one-half a regular step.

When your fingers walk up the inside of a piano keyboard, it takes only a "baby-step" to move to the next key, but a full step to skip over a key. Starting from C and following this pattern you step only on white keys. In an auditory sense, remember that a baby-step is said to be equivalent to one-half a regular step.

You may already know that going up from white key E (to F), or from B (to C) takes only a baby-step. Going up from any other white key, a baby step would take you to a black key.

The black key is higher pitched (sharper or spicier, as shown by the # symbol) than the white key to its left. C# and F# are the black keys immediately to the right of the C and F keys, respectively, as shown on the piano keyboard at right.

The black key is higher pitched (sharper or spicier, as shown by the # symbol) than the white key to its left. C# and F# are the black keys immediately to the right of the C and F keys, respectively, as shown on the piano keyboard at right.

Let us now walk up the inside of the keyboard, following our previous stepping pattern (Step Step Baby-step, etc.), starting from the white D key on the left:

D step-to E step-to F# baby-step-to G step-to A step-to B step-to C# baby-step-to higher D

What we have here is the D collection of notes, and if written starting and ending on D, as above, it is known as the D-major scale.

D E F# G A B C# higher-D

If you have a double-row accordion with a D row, then you are playing the D-major scale when you play the following buttons:

3 step-to 3* step-to 4 baby-step-to 4* step-to 5 step-to 5* step-to 6* baby-step-to 6

You may note that this is identical to the buttons and steps in the previous section for the C-major scale. That is the great thing about true diatonic accordions: If you can play a tune on one diatonic row, you can play it on any other row, on any other true diatonic accordion. As a result, these accordions are said to be "transposable".

D step-to E step-to F# baby-step-to G step-to A step-to B step-to C# baby-step-to higher D

What we have here is the D collection of notes, and if written starting and ending on D, as above, it is known as the D-major scale.

D E F# G A B C# higher-D

If you have a double-row accordion with a D row, then you are playing the D-major scale when you play the following buttons:

3 step-to 3* step-to 4 baby-step-to 4* step-to 5 step-to 5* step-to 6* baby-step-to 6

You may note that this is identical to the buttons and steps in the previous section for the C-major scale. That is the great thing about true diatonic accordions: If you can play a tune on one diatonic row, you can play it on any other row, on any other true diatonic accordion. As a result, these accordions are said to be "transposable".

7. Musical Keys

When playing your accordion with other instruments, such as guitars, it is important to know that you are all in the same "key". If you have only one accordion, say in the keys of G & C, you will all need to play in one of these keys.

Although not absolutely necessary, do you want to know what is meant by a musical key? When we say that an outer row of a double-row accordion is in the key of G, it means that buttons 2 to 11 yield tones that correspond to the G collection of notes (G, A, B, C, D, E and F#). When we say that an inner row is in the key of C, it means that buttons 2 to 10 yield tones matched to the C collection of notes (C, D, E, F, G, A and B). Note that these two collections differ in only one note (F# versus F).

Now it's time to move on for a brief look at the basic BUTTON ACCORDION layout.

When playing your accordion with other instruments, such as guitars, it is important to know that you are all in the same "key". If you have only one accordion, say in the keys of G & C, you will all need to play in one of these keys.

Although not absolutely necessary, do you want to know what is meant by a musical key? When we say that an outer row of a double-row accordion is in the key of G, it means that buttons 2 to 11 yield tones that correspond to the G collection of notes (G, A, B, C, D, E and F#). When we say that an inner row is in the key of C, it means that buttons 2 to 10 yield tones matched to the C collection of notes (C, D, E, F, G, A and B). Note that these two collections differ in only one note (F# versus F).

Now it's time to move on for a brief look at the basic BUTTON ACCORDION layout.